How Outdated Data Privacy Laws Might Affect You—and Your Data

David Kalat

After 180 days, your data can be accessed by authorities without a warrant, thanks to a 1980s law.

In August 1985, Creative Computing magazine gushed over a new “bargain price” hard-disk drive that had just hit the market.

“That's right,” the reviewer noted. “First Class Peripherals offers the Sider, a hard disk drive with 10 MB partitionable among four operating systems for $695.”

By the end of 2019, the average flash memory capacity for smartphones is expected to reach 83 GB, up from an average of 43 GB at the end of 2017. The average smartphone user carries around a device with more than 8,000 times the storage capacity of what a high-end computer user would have been delighted to buy in 1985.

Today’s digital citizens need not live with the limitations of 1980s computer technology. However, they must live with the limitations of 1980s computer laws.

1980s data storage laws … in the 21st century

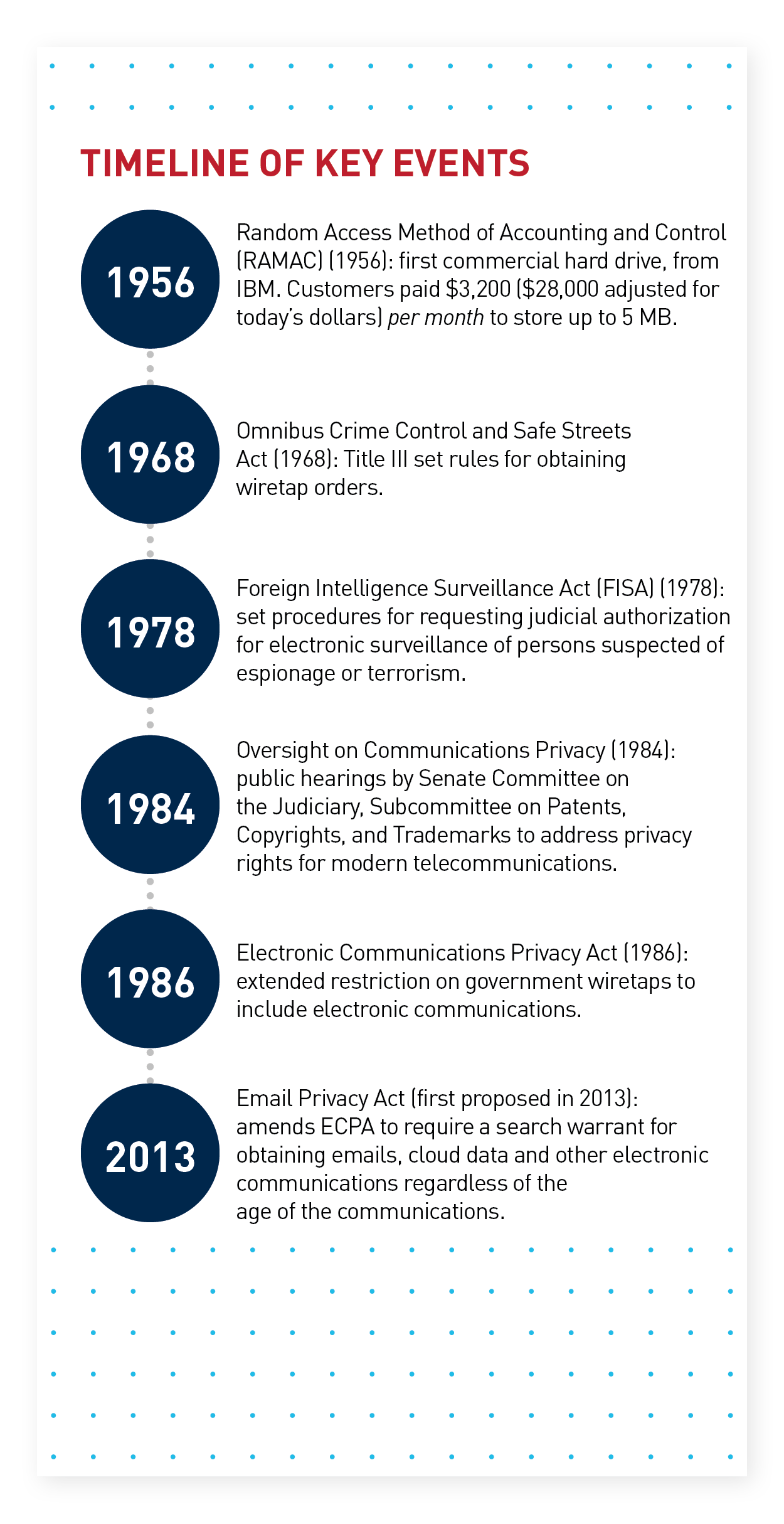

Since shortly after the Sider went on sale, US law has recognized two levels of privacy protections for emails and other stored electronic communications—based entirely on the question of whether those communications have been stored for longer than six months. Under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), electronic communications can only be accessed by law enforcement or government agencies pursuant to a search warrant, unless the communications have been stored for more than 180 days. In that case, a court order will suffice.

Why the distinction? In the face of the extraordinary high data-storage costs—i.e., when 10 MB for $695 was considered a good deal—1980s lawmakers figured people would read, reply to, and delete emails quickly and routinely, and would only store them long term if they needed to keep them as business records. They also figured a person or entity who deliberately saved something (or a lot of somethings) for more than six months would likely understand the privacy issues noted above.

Three decades later, data storage is exceedingly cheap, and people routinely and unthinkingly keep communications and documents almost indefinitely. It’s doubtful most people even know about the privacy standards that apply to their data, or how they came about.

How the ECPA came to be

In early 1984, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont) became aware of a problem with wiretapping regulations set forth in Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA). The laws only governed communications that could be heard and articulated the circumstances under which wiretapping would be permissible. Developments in telecommunications had outpaced FISA, and voice calls increasingly were no longer “hearable” in transmissions, as they were conveyed as digital data packets. That put them outside the explicit protections of the law.

After confirming with the attorney general that “nonaural” calls did not require a warrant or nonconsensual interception under FISA, Leahy held hearings to publicize the problem. Invoking the Orwellian prospect of unlimited warrantless wiretapping—the hearings, perhaps too perfectly, were held in 1984—Rep. Robert Kastenmeier (D-Wisconsin) introduced a bill to bring traditional privacy protections to modern technology. That bill would evolve into the ECPA, which President Reagan signed into law in October 1986.

The ECPA provided explicit privacy protections for wire, oral and electronic communications at the time of the communications, during transmission, and—crucially—when they are stored on computers. This applies to email, telephone conversations and data stored electronically. The law’s architects were even thoughtful enough to consider the distinction between message contents (which enjoyed a heightened degree of privacy) and metadata (more easily disclosed to government agencies and third parties), using the analogy of the outside of an envelope that shows the sender, receiver and date of transmission, but not the content of the communication.

The creators also carefully distinguished between “electronic communication services,” which facilitate the sending and receiving of wire or electronic communications, and “remote computing services,” which provide storage or computing resources to subscribers or consumers. These distinctions have proven robust and useful and brought the ECPA’s reach to contemporary cloud-computing systems and other technologies that probably sounded like science fiction in the mid-1980s.

When technology upends bedrock assumptions

While much of the ECPA was ahead of its time, other parts haven’t aged as well—notably the oddly specific distinction about 180 days being a marker for when the privacy protections on stored communications suddenly erode. In March 2019, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals wrangled with a convoluted case in which a person, Patrick Hately, had his webmail account accessed by a third party and used against him in a divorce proceeding. The intruder’s defense relied upon a reading of ECPA that treated Hately’s opened emails as undeserving of the privacy protections granted to the unopened or deleted emails.

There have been recent, but unsuccessful, attempts to require authorities to obtain a search warrant before accessing messages, regardless of when they were sent or received, from a subject’s email provider. ECPA architect Leahy and a consortium of technology companies and privacy advocates supported these attempts, but they have faced institutional opposition from Senate Republicans who do not want to vote to make law enforcement’s job any harder. And given current political polarization, it is unclear whether modernizing privacy rules around stored data has a chance at success, at least in the near term.

That means that for now, authorities don’t need a search warrant to collect emails from your email provider once the 180-day threshold is reached—even if the law behind it is an absurd relic of a bygone era of floppy disks.