Understanding Infrastructure Disputes: Financing Strategies and Rate of Return

In the second guide from our series on Understanding Infrastructure Disputes, Calvin Qiu looks at how infrastructure projects are financed and how long-term investment decisions are made based on rate-of-return calculations.

Private investment approaches to infrastructure projects

Infrastructure projects can be financed through a combination of public and/or private investment.

In infrastructure projects involving private capital, there are two broad approaches to financing, depending on whether the project appears on the sponsor’s (i.e. equity investor’s) balance sheet.

(I) In on-balance sheet financing, the project sponsor provides equity and debt capacity, and the infrastructure project appears on the balance sheet of the sponsor. These projects are typically part of the sponsor’s core business (e.g. a electricity company building and operating a power plant). Lenders have recourse to the primary sponsor, and overall financing cost is typically cheaper, by virtue of the backing provided by the sponsor.

(II) In off-balance sheet financing (or project finance), a separate project entity is formed, and the assets and liabilities of the infrastructure project are ringfenced from those of the sponsors. Projects financed with project finance typically have limited or no recourse, meaning that sponsors could in theory walk away from a failed projects (although they could still suffer from reputational repercussions). Correspondingly, the cost of financing for off-balance sheet projects is typically higher.

The choice of financing approach depends on factors such as the size and risk characteristics of the project (larger and/or riskier projects are more likely financed using project finance), and whether the sponsor considers the project to be a part of its core business.

Irrespective of the approach used, when evaluating infrastructure investment opportunities, it is necessary to weigh initial outlay against expected future cash flows to evaluate the attractiveness of a project. When presenting expected cash flows over a project’s lifecycle, it is important to do so on like-for-like basis, by taking into account the time value of money, which is explained on the following page.

Time value of money

Time value of money is based on the idea that receiving a dollar today is preferable to receiving a dollar tomorrow. When receiving a dollar today, it is possible to lend it for interest income (or otherwise invest it); that interest is given up if the dollar is instead received tomorrow.

When comparing cash flows at different points in time, it is therefore necessary to convert these into ‘present value’ measures. Cash flows in the future are discounted based on their timing and an appropriate discount rate. The discount rate can represent the rate of return of the alternative investment opportunity, or the cost of capital (i.e. how much it would cost for the investor to obtain additional financing on equity and/or debt markets).

Internal rate of return (IRR)

A measure that is commonly used in project appraisal is called. In an IRR calculation, the timing and magnitude of expected cash flows over a project’s lifetime are set out, such as the initial outlay (cash outflow), expected future income streams (cash inflow), and anticipated capital expenditure for repair and maintenance (cash outflow).

The IRR is the discount rate at which the present value of all the positive cash inflows and negative cash outflows sum up to zero. This represents the rate of return of the investment, in other words, a project with higher IRR is financially more attractive.

IRR and investment decisions

IRR provides a basis by which investment opportunities can be evaluated. Potential investors can compare the IRR of a project against their cost of capital: if the IRR is greater than cost of capital, then in theory the investor would gain a net benefit by investing (since it would earn an return in excess of how much it costs to raise the capital).

However, future cash flows are inherently uncertain, and in practice investors may only invest in projects with an IRR above a threshold level (e.g. 20% is a common rule-of-thumb threshold for private equity investors).

IRR also enables the comparison of the attractiveness of different investment opportunities. If the potential investor is capital constrained (and can only make a limited number of investments), it can prioritise opportunities that have a higher IRR. For projects with similar risk characteristics, the ones with higher IRR are more attractive.

Different measures of IRR

There are different IRR measures, the relevance of which depends on the type of investor:

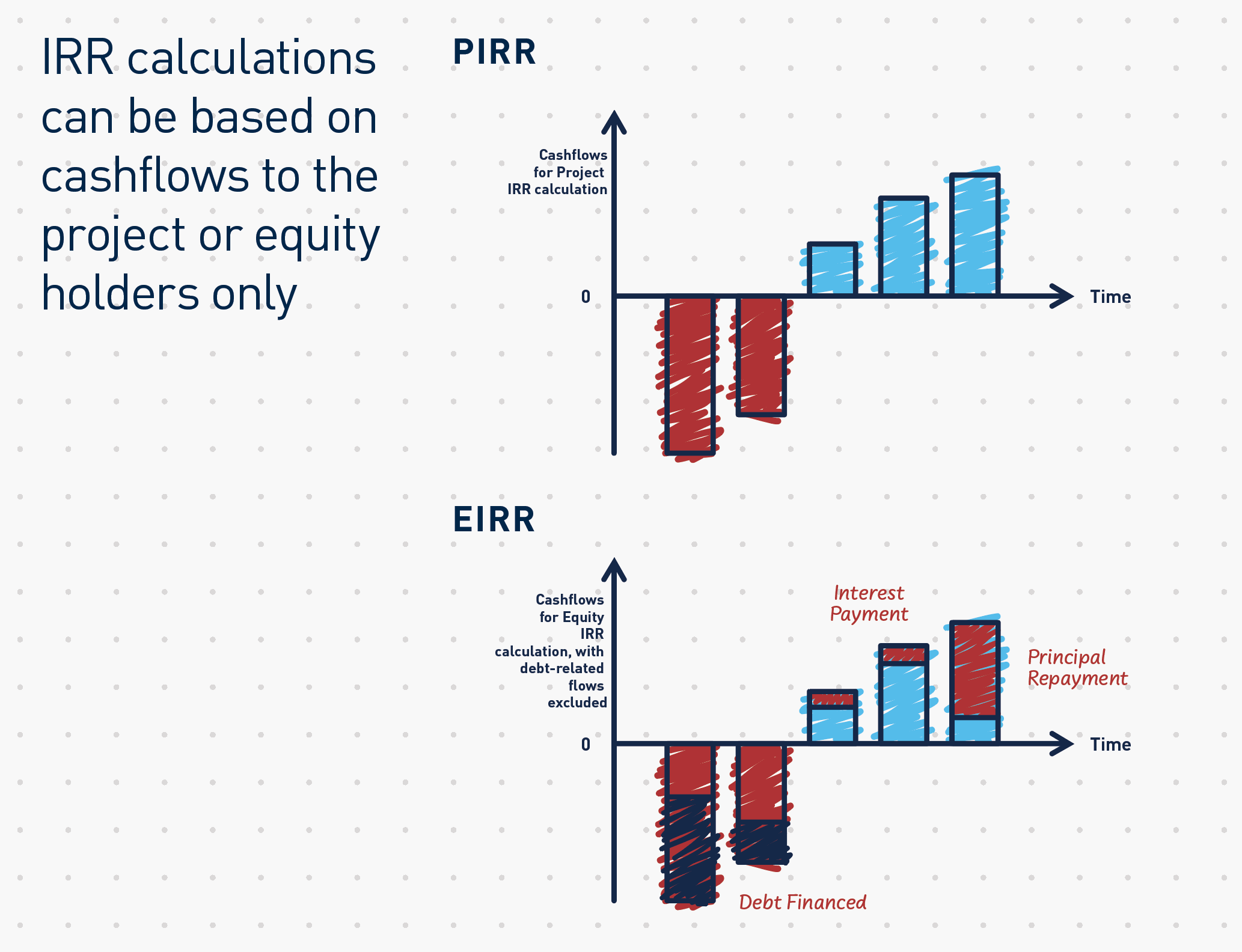

(I) Project IRR (PIRR) considers the project’s overall rate of return by considering all cash inflows and outflows to and from the project.

(II) Equity IRR (EIRR) considers the return to an equityholder in a project only. Instead of considering all cash flows, it only considers those flows relevant to an equity holder. In particular, debt-related cash flows are excluded, outlay; and principal repayments and/or interest expenses have to be deducted from incoming cash flows.

PIRR is typically used as a metric for on-balance sheet projects. Because the project appears on the sponsor’s balance sheet, the sponsor is interested in the rate of return at the project level, and would compare this against its cost of capital.

For off-balance sheet projects, the sponsor’s stake is limited to its equity investment in the project, and the sponsor is therefore interested in the EIRR. This is compared against the sponsor’s equity hurdle (or threshold) rate – if the EIRR exceeds the equity hurdle, it is a viable candidate for investment.

In this series, Peter Bird and Calvin Qiu set out the elements of infrastructure projects which are key to understanding the disputes they frequently become involved in; and the context and insights which economists and forensic accountants will apply in their analysis and assessment of these cases. Read part one, “Stakeholders.”